I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness is writer and racial justice instructor Austin Channing Brown‘s declaration to those not in the know that whiteness, as a racial construct, is something that must be broken. To use the opening line of her book, “White people are exhausting.”

As she discusses in my interview with her, that first line is bound to turn some people off. But I’d say to think of that line as bitter medicine; it doesn’t taste very good going down, but once you get past it, you realize that there’s a healing quality behind it. Such is the case with the entire book. For many who aren’t aware of the types of micro and macro aggressions black people–black women in particular–face on a daily basis, this book might seem like an attack. But if it’s viewed as such, it probably just means you aren’t at the place yet in your own personal journey to empathize with what Brown has to say about her experiences growing up as a black woman, from her family lauding black excellence to her experiences in black schools and churches, to family tragedy involving her cousin. There is a lot of anguish that comes from being black in a white world–more specifically, a white world that isn’t always taught to empathize with others outside of their race or background–but there are a lot of triumphs as joys as well, such as sharing what Brown called a “secret language,” experiencing similar cultural touchstones, and understanding similar struggles.

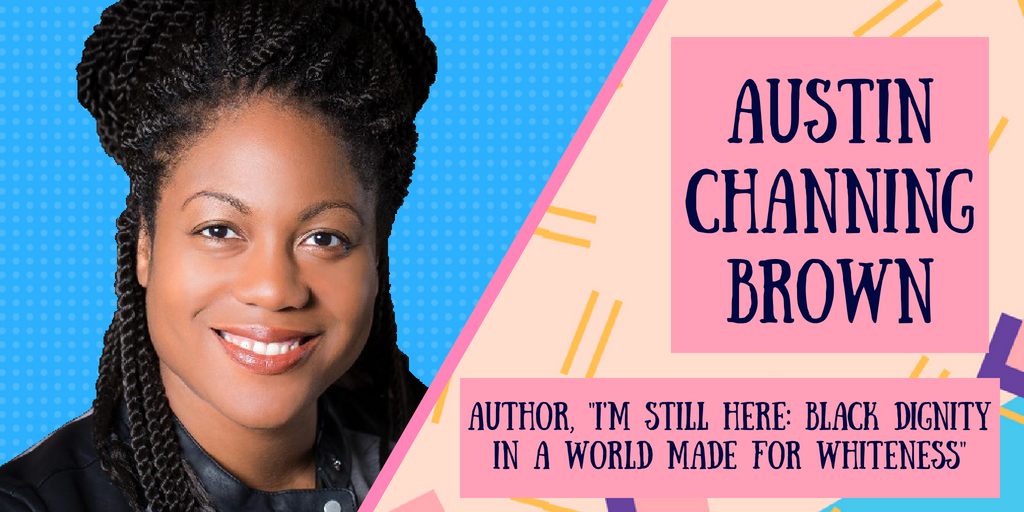

JUST ADD COLOR: What inspired you to write the book? Why did you think the message was one people needed to hear?

AUSTIN CHANNING BROWN: I was really interested in writing a book that made black women feel less alone. I grew up around white spaces educationally and most of my working experience has been in white organizations. As I traveled, I realize there were a lot of folks having the same experience as me. Every time I spoke at a church or university, there were always a handful of black women who were just keep on keepin’ on. It made me realize that it’s really easy for those in predominately white spaces to feel alone and isolated. The truth is there are a lot of us in white spaces…and I wanted to write a book that showed you’re not alone and if you’re having some experiences that are difficult or exhausting, you’re not making it up.

Reading the book got me to thinking about my own early experiences. In my household, I was raised with only black dolls in the beginning and overall, I had no white dolls growing up. I was raised watching Roots and reading American Girl Addy books as well as learning about other cultures outside of whiteness. On top of that, I’m from Birmingham, AL, one of the epicenters of the Civil Rights Movement, and that legacy is still felt every day thanks to the real life monuments that surround us. With all of those experiences, I felt like those helped me through harder times I might have faced in my predominately white high school. Similarly, you talk in the book about some of those experiences of being in white spaces and how your parents had images of blackness in your home, including your childhood reading books by black authors. What other lessons in blackness do you think your parents instilled in you as a child? Or were there aspects of black art that helped buoy you through your life?

That’s a great question. I do remember my mom was very adamant about the black Barbie dolls too. Back then it was so much harder to find dolls and books that reflected us. I remember my mom having to reach back to the seventies. I remember the book Honey I Love was a staple, Snowy Day…I do remember my mom having to work really hard because I don’t remember my school library having any books by black authors or with black characters. I do remember my grandmother, who I stayed with a lot after my parents divorced, she was an artist. She was a home economics teacher for many years back when home economics meant you also had to do art. She was the first black artist in my life; I remember wanting to be an artist when I grew up because she was an artist.

I do feel like my parents trying to combat the white education I was receiving. I remember Jesse Owens being one of the first people I learned about at my dinner table; I just remember my parents being really proud of who we were. There was no shame about it; there was no desire to hide anything about it. I think I was almost arrogant about it, knowing about our history and our authors and our music. It made me feel special, I think that I had this secret knowledge that my white classmates didn’t have about the world. I was very grateful for that growing up.

There is a lot in your book about being the black person in white spaces, whether that’s in your neighborhood, your classroom, or in the corporate setting. How did writing about those experiences help you come to grips with them and how they might have affected you?

I worked really hard as I was writing not to write out of trauma or out of open wounds, but to me, things that are done and I’m not very emotional about anymore so this didn’t become like a private journal. I also wanted to write about experiences would probably be shared across the country instead of some of the extreme thing I’ve experienced because I didn’t want the book to be out of reach or to be so specific that people of color wouldn’t be like ‘That never happened to me’ or white people would be like, ‘I’d never do that.’ I wanted to root it in a shared reality so that maybe everyone hasn’t experienced everything, but I wanted there to be some very, very similar experiences.

The craft of writing the book was really about trying to put the emotion back in it when I felt those experiences happen. The only thing that was really difficult was writing about my cousin, and I presume I’ll always be emotional about. But everything pertaining to white folks was an attempt to remember how it felt then, but nothing that I’m thinking about currently.

For me, the book was more of confirmation that other people of color or black people have felt this way or still feel this way. How do you think this book has affected white readers, since a lot of what you talk about is probably stuff they have no idea about?

As I wrote people in terms of audience, I really prioritized people. First was black women, then people of color, and then white people. I was very aware of how I thought black women would react to reading this book, then people of color and then white people. I can’t say I ignored the white gaze–I’d like to say I did, but it’s not true. What I did do was think to myself that the white audience I suspect will read this book are already further along in their journey. So people who aren’t convinced they should care about racial justice or are still asking about white privilege or if they have white privilege, they probably aren’t going to be reading this book.

Really, I decided that with the first line, “White people are exhausting.” I figured if you’re at the beginning of your journey, that sentence is probably not going to appeal to you; if you’re standing in Barnes and Noble reading that you might just put the book back down. But that helped me to not compromise my own prioritization and believing that there are white folks out there who are wanting to do the hard work, who are already in diverse spaces and are wanting to see how they can make themselves better or how they can be better supervisors or teachers and are wanting to continue to open their eyes in the ways they subtly participate in white supremacy.

As you can imagine, I’ve gotten some mixed reactions! I’ve definitely gotten some emails saying I’m the real racist and all that jazz, but by and large, the response from white folks has been one of gratitude and the primary message I get from white folks is that it was really hard and they had to put the book down a lot, but they’re glad they read it. I’m appreciative of the openness the book has received, because I was expecting a lot more trolling, to be honest.

You talk about racial erasure in our political and social spheres. We’re going through an aspect of that right now with the immigration crisis, where too many people are saying “this is not who American is,” when it is exactly who American has been since its inception. How do you feel about the constant erasure that continues to take place?

It really makes me sick, honestly. What we’re doing in our country’s name makes me sick, but also to see the cycle repeat itself over and over and over again, it can really weigh on your hope. How have we arrived back here again? Indigenous genocide, slavery, Japanese internment-how have we come back here again? It’s really frustrating to see America repeat these same sins over and over and over again and act like it’s brand new. I’m really grateful for the role of historians in moments like this. I’m really grateful for those who are connecting the dots. But it is difficult to not be very frustrated. Maybe frustrated on a good day, raging mad on a bad day.

In the book, you talk about the weight of being the person of color who is looked upon to bear her soul to her white coworkers who look to people of color to explain the world around them and how this labor is taxing. With the release of the book and the conversations its caused, how do you contextualize this type of labor? Does explaining blackness become, in its own way, more laborious or does it become freeing?

That’s a great question! I think me talking and teaching about racial justice has been a journey. I think those of us who teach or write books or do workshops can have a tendency to feel like we’ve always been woke just because the work requires us to be the expert in the room. I am so aware of how much I have learned along this journey and the way I did not do so great when I first started out. One of the early mistakes I made in terms of labor was allowing white folks to ask questions however they wanted whenever they wanted and feeling like I had a responsibility to all the black community to set the record straight. That became very unhealthy, being that person in the office answering questions and not getting my work done…and getting emotionally worn down.

I remember being stopped in a hallway one day and a guy saying, “Hey, I went to one of the three classes you taught, but I never came back after that first class, but I have a question for you.” I was like, “You know I teach a class on this, to came to the first one and didn’t come back for the last two, and now you’ve decided to stop me in the middle of the hallway to ask your race question? I think you should come to the next class!” That was an a-ha moment as I was standing there. Previous to that, I definitely would have just done the labor.

The second thing I was not good at was I didn’t really talk a lot about blackness, actually. Early in my career, I really talked a lot about white supremacy, white fragility, white guilt, how white people were feeling, what white people were thinking. So much of the content still centered white folks. But because I was talking about racial justice, I felt like I was centering myself. And it wasn’t until I was sitting in another class I was teaching, and a white teenager said as innocently as he wanted to, that after listening to all the dialogue in our class that day, he was glad he was a white guy because he wasn’t sure he could handle all the oppression and stories he’d heard people of color describe discuss in the class that day.

Part of me was like, “He’s listening–he’s understanding that in all of his white maleness, he doesn’t have the resiliency to deal with what we deal with.” But on the other side, my brain was thinking, “Oh, you’ve only heard the terrible things. You have no idea that I have no desire to be you!” I love being a black woman. There’s no way I’d choose to be anything else! I love being a black woman, and that was the day I decided that celebrating blackness had to start being was something I’d have to do while talking about racial justice. To only talk about whiteness was the draining part. Being able to celebrate who we are, to celebrate our art, Beyoncé, hip-hop–there’s something very freeing for me about that that doesn’t feel like labor at all. It honestly feels like the missing piece of my work that I’m really glad I’ve found.

I heard Ta-Nehisi Coates say how often he would be sitting in white spaces, like the workplace, and how white people would start talking about musicians and artists and pop culture things that he had never heard before and how nobody stopped to explain who these folks were; he just had to catch up roll with it or get it via context or google it later. I think I’ve taken on some of that approach; I don’t always explain everything. I try to talk about blackness the way we would if you and I were just having a conversation and not explain every little detail so white people are experiencing what we experience on a very regular basis. There is something very fun about that, I will not lie. Like, “I gotta go get a relaxer, child!” and not explain what any of that is. It feels like part of the resistance.

It does take it from the academic world because I think that’s where some of the hesitancy is when it comes to some white people learning about blackness and their place within the racial framework of whiteness; blackness is often taught as a fixed, historical object instead of as a living, changing thing. There’s this idea of “I can set it down after I’ve learned about it and use it when I need to.” If more people viewed it as a living thing, I think more people would be willing to learn about it and their role in all of this.

I completely agree. And I think when we talk about it without doing all of the explanations, I think white people begin to realize there’s so much more that they didn’t know. This is a really stupid example, but when Beyoncé came out with Lemonade and she dropped that Becky line, I thought about how there are a whole lot of white people who didn’t know that for years, black women have been calling white women Becky. There are millions of white women who are about to learn about this secret language that black women share.

And even though that’s a really stupid example, I think when we begin to talk about blackness as normal and not something exotic or weird or as you said an “object,” when we talk about it the way we live it and how we love it, I think white people’s eyes are wide open because they have no idea. They’re like, “I know who Martin Luther King is, I know how Rosa Parks is.” There’s so much more to being a black person in this country.

Readers might come away with the book feeling like they need to rethink their perception of society. What advice would you give people who want to start examining their own experiences with race and their worldview? Also, for black readers who just might be coming to terms with their blackness, what advice would you give for them to help them on their journey?

The thing I find myself saying to black folks over and over…is actually just repeating the title of the book. You are still here. I have a hard time explaining the spiritual depths of that moment, sharing that moment with people who have been hurt and disappointed and erased and have been performing a lot of emotional labor without much gratitude and almost lost themselves. To be able to look in their faces and say you’re still here matters a lot to me. To those folks, I would say that you’re not making it up–white people really are exhausting, and you get to rethink how you do it. That’s maybe the core of my message to people of color especially black women, because my story was a journey. There are things I used to do that I don’t do anymore. That’s my message to black women; you can change your mind how you want to do this…if something doesn’t feel healthy to you, you get to change your mind.

The common question I get from white people is, “What do I do now?” To them, I always say, “I have no idea.” But I want to say there is something you can do. If you’re a teacher, maybe you should rethink your classroom. If you’re a great fundraiser, maybe you should think about supporting black women. If you’re in a position to hire folks, maybe there are some hiring practices you can change. No matter where you are, there’s something you can do. It’s your responsibility to figure out what that is. I hope the book is inspiring people to figure out what that is.

What would you want the legacy of your book to be?

Oh man! That’s a good question. This might be wildly arrogant, and I don’t eman it to sound arrogant, but I really hope this book is part of pushing the racial justice conversation forward. I hope it’s another step that black folks are taking to say ‘This is how we do this now.’… I’m so aware that my book is probably not the best introduction to Racial Justice 101, but I hope to those that are committed that it becomes a second breath of air, a marker on their journey that let’s them know they can keep going, white or black. ♦